Colorado State University faculty member Jen Weaver’s research on the recovery of consciousness of people with severe traumatic brain injuries helps give a voice to those who often cannot speak.

Weaver’s studies funded by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and American Occupational Therapy Foundation also bring perspectives from those patients’ caregivers – family members – so they can better advocate.

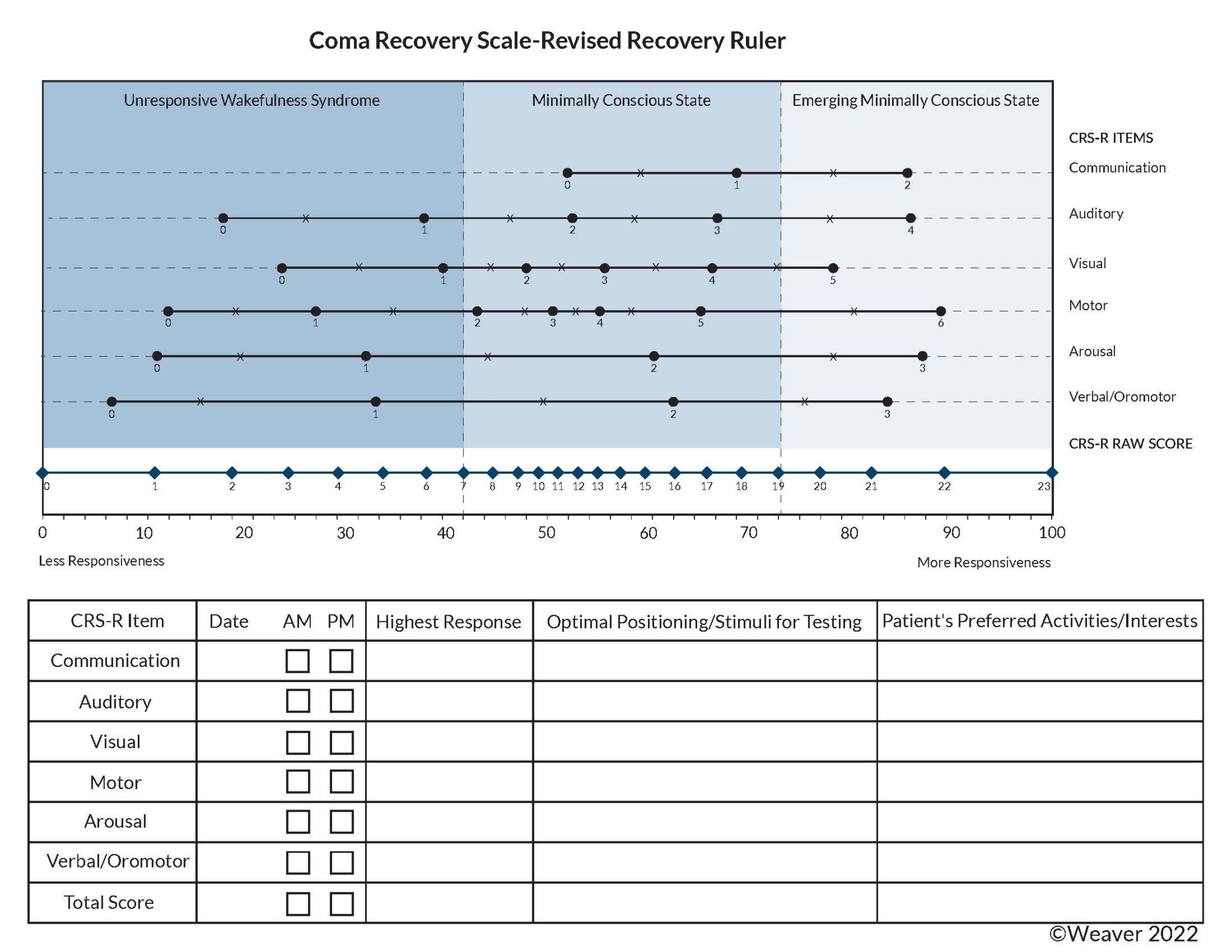

One prong of Weaver’s research is improving assessment tools like the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) – developed by Joseph Giacino – to help patients’ families visualize their loved ones’ status.

“One challenge we have in rehabilitation is most of our assessments are ordinal measures. All that means is we know that a one is better than a zero, a three is better than a two, but the difference of one is not the same along the scale,” said Weaver, an assistant professor in CSU’s Department of Occupation Therapy.

“That is published in the Journal of Neurotrauma. We transformed it into an equal interval ruler, which is similar to how we measure temperature or use a yardstick, where we can truly measure and interpret the difference of one unit.

“The transformed measure is on a 0 to 100 scale,” Weaver added. “It is comprehensible, whereas the original scale is 0 to 23 points. And our preliminary evidence indicates that a person needs to make about 10 units of change on the transformed measure to indicate a true change.”

TBIs are common

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that there were about 223,000 traumatic brain injuries (TBI) or related injuries in 2019 and about 64,000 TBI-related deaths in 2020 – about 611 hospitalizations and 176 TBI-related deaths per day. Those numbers do not include TBIs only treated in ERs, primary care or urgent care, or cases that go untreated.

The CDC also estimated that the total annual health care cost of nonfatal TBIs in 2016 was more than $40.6 billion, including $10.1 billion by private insurance, $22.5 billion by Medicare and $8 billion by Medicaid.

“This unconscious population can’t advocate for themselves, whereas other people with a brain injury may have the capacity to advocate,” Weaver said. “We have conducted interviews with a lot of rehabilitation practitioners as well as family caregivers; we had more than one family caregiver say that they had to go to their state representative to advocate for rehabilitation for their person.”

Weaver said patients with disorders of consciousness (DoC) should be referred to rehab services in the hospital and receive these services in post-acute care.

“One post-acute care setting, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, requires patients to participate in at least 15 hours of therapy each week,” she said. “Patients in DoC are not always referred to these intensive rehabilitation settings because there is a stigma that they cannot ‘participate’ in therapy.”

Weaver said some patients with TBIs are military members who are at risk due to combat or training exercises. “I think the fact that our study aims to improve the diagnosis and prognosis for severe TBI survivors, while also trying to provide transparent clinical assessment data to the family, was of interest to the Department of Defense,” she said.

Most TBI patients and their families must navigate therapeutic options such as physical, occupational and speech pathology/language therapies.

“In terms of receiving rehabilitation services like occupational therapy and physical therapy – especially in a more intensive setting – medical professionals look at your ability to return home and participate in therapy for three hours a day,” Weaver said. “And I would argue, what does participation really mean, because this population can benefit from therapy services. But we have barriers to improving access to more care for this population – such as a stigma that these folks cannot participate – even when science is telling us we can see them recover different functional areas five and 10 years after being injured.”

Expert voices

Like in previous studies, Weaver got help from two women whose sons died after spending months or years with disorders of consciousness.

Trish Kot and Paige Ford are “lived-experienced consultants” who have asked questions of other families in earlier research. Their input was instrumental in studies like “No One Listens to Me”: Understanding Recovery When Patients Cannot Speak for Themselves and follow-up research.

“One thing that I try to do in all of my research is to amplify the caregivers’ voices and make sure that’s a part of the research process,” Weaver said. “Those two women, they’re amazing.”

Kot, whose son fell out of a pickup in 2000 and died in late 2003, said having a reference point will aid families.

“I never had anything concrete to hold in my hand and look at and evaluate,” Kot said. “There was nothing. I think Jen’s research with this idea of the Recovery Ruler would be so beneficial to the family to measure progress, if any, and try to evaluate their loved one with some transparency of clinical data.”

Ford, whose son was in the military and was in a motorcycle accident in 2013, said she is proud to work with TBI research.

“It was not good with the health care system or the doctors,” Ford said. “I just felt like we were brushed off more than anything. So, the research means a lot. It is too late for my child, but I can help others.”

More data coming

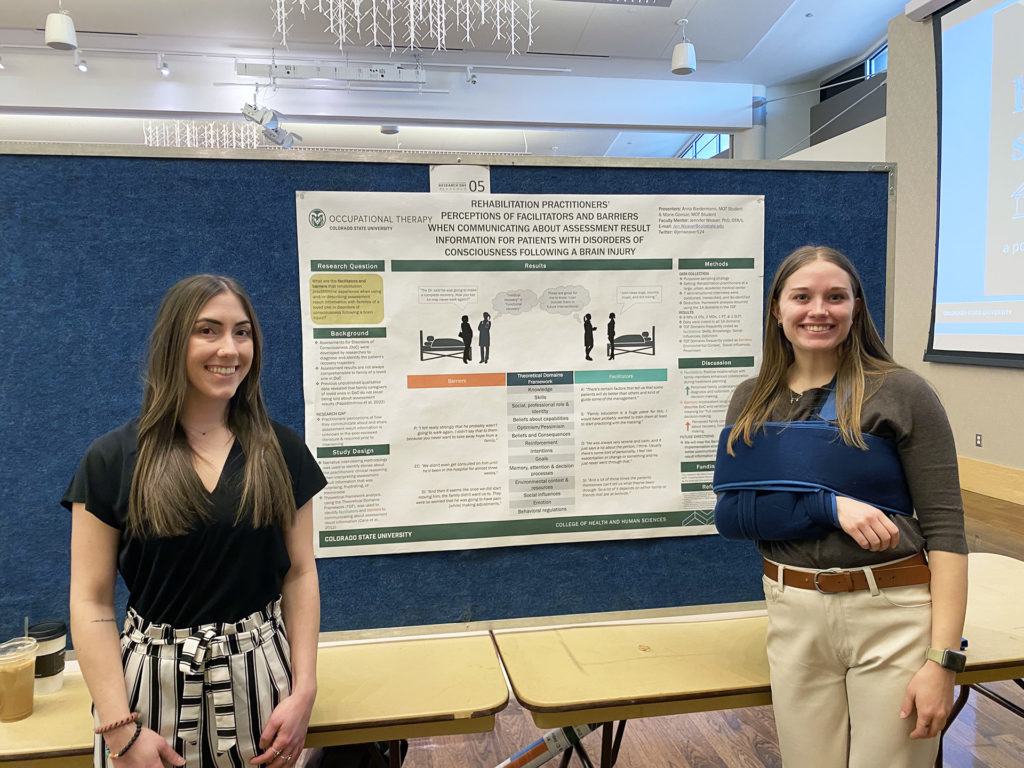

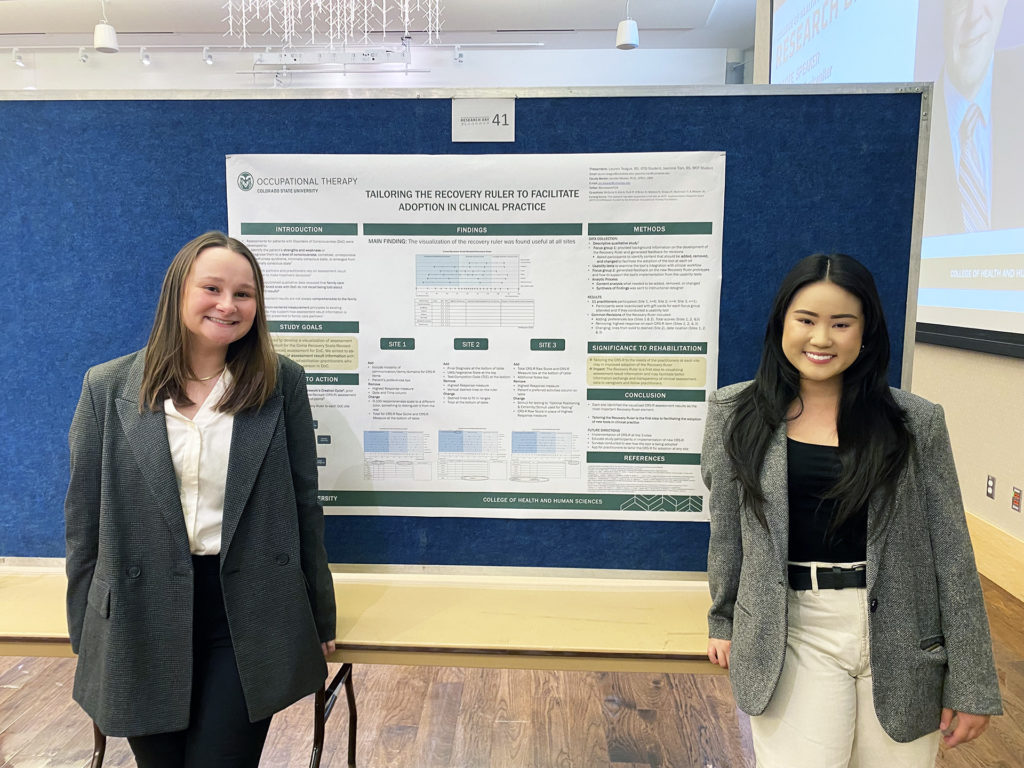

Two pairs of Weaver’s students presented posters during the College of Health and Human Sciences Research Day. Jasmine Tran and Lauren Teague showed a poster on tailoring the Recovery Ruler. Anna Biedermann and Marie Gonsar presented barriers and facilitators to communicating about result information.

Weaver said four hospitals – Memorial Hermann in Houston, Spaulding Rehabilitation in Boston, Shirley Ryan AbilityLab in Chicago and Craig Hospital in Denver – include co-investigators who recruit practitioners to start using a customized Recovery Ruler, hoping that it will facilitate better communication to family about recovery of consciousness. Weaver’s team will collect more data as it becomes available from engaged practitioners.

“The more I stay on the research side, the less in tune I may be with clinical practice, and I am aware of that, and I want my work to be meaningful to practitioners and to the family members of patients with severe brain injuries,” Weaver said. “I don’t feel like I could do the work without the engagement with them.”

The Department of Occupational Therapy is part of CSU’s College of Health and Human Sciences.