A survey of Colorado mental health professionals in K-12 schools shows that more than 25% of their students became disengaged when they shifted to remote learning due to COVID-19 – and most of those were low-income students or students of color.

Researchers in Colorado State University’s School of Social Work surveyed 58 mental health professionals in four Front Range school districts during May and June of 2020. They found that already existing disparities were exacerbated by the pandemic.

“You can see how the systemic racism that existed before the pandemic just expanded these inequities,” said one of the leaders of the study, Assistant Professor Tiffany Jones. “This felt really urgent, and at the time we asked, ‘Why aren’t people talking about this more?’”

Associate Professor Anne Williford, another study leader, added that low-income populations and people of color are more likely to be employed in low-wage, frontline jobs, giving them higher chances of exposure to COVID-19 and less time to help homeschool their kids. Services such as food banks saw increased demand and competition, making things even harder on families and students’ mental health.

‘Doom, isolation and uncertainty’

“This week alone I’ve had six kiddos go to the hospital because of the feeling of impending doom, isolation and uncertainty coupled with typical kid angst,” one survey respondent said. “It’s been heartbreaking to watch.”

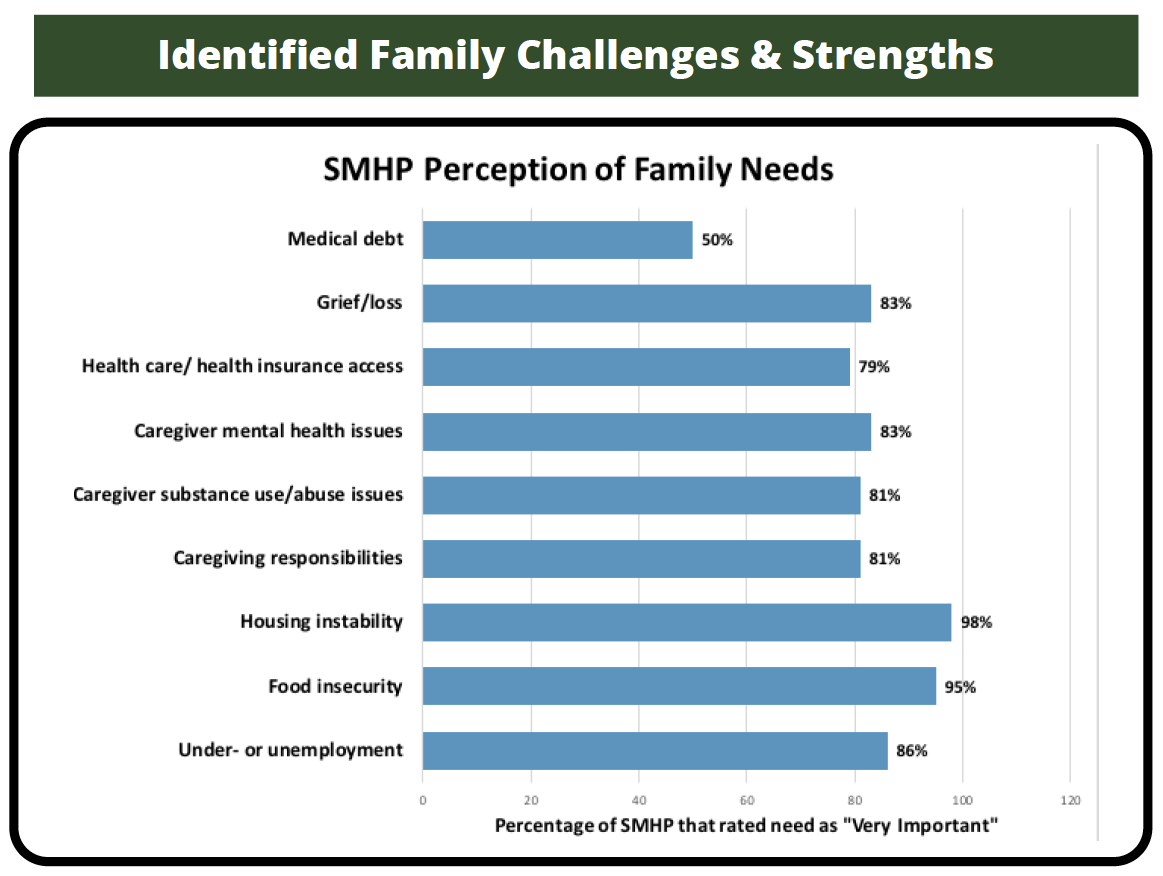

According to those surveyed, the most frequent areas of concern for families were under-employment/unemployment and food insecurity, followed by housing instability, caregiving burden and caregiver mental health and substance use/abuse issues.

Jones and Williford were the lead authors of a paper about the survey results published May 31 by Oxford University Press.

Jones said many factors contributed to the high level of disengagement seen among students of color and low-income students when they were forced to do their schoolwork at home, from technology to security.

“One computer device per family used to be fine, but it’s not now,” she said. “And what if your house actually isn’t a safe place to be, and school was your safe place? For anyone who was in a slightly hard situation before, it got so much harder.”

Complete disengagement

Survey respondents said a significant number of students dropped out of their schooling altogether after the switch to online learning.

Report assesses dropout rates in spring 2020

A related study conducted by CSU’s Regional Economic Development Institute examined how the pandemic may have affected the number of students on northern Colorado campuses who finished the Spring semester of 2020, compared to the previous year.

Niroj Bhattarai, an assistant professor of economics at CSU, and Economics Faculty Lead Jaren Seid of Front Range Community College-Larimer Campus, found that the switch to remote learning caused an uptick in withdrawals, incompletes and applications for an “unsatisfactory” grade among college students.

They found that the older students were, the more likely they were to not complete the Spring 2020 semester. While a greater percentage of males dropped out than females overall, women had a higher probability of noncompletion in Spring 2020. Both groups saw the biggest uptick in incompletions in the 35-39 age range, where they are more likely to have school-age children and jobs.

The researchers concluded that the switch to remote learning placed a disproportionate burden on nontraditional students, especially women. They encourage public-policy changes to improve things like child-care services and subsidized broadband connections.

“One of the biggest impacts was the degree to which students were disengaged,” Williford said. “Some disengaged completely in the spring of last year and had no contact with the school. That was a striking finding for me.”

Students’ withdrawal sometimes prompted police to visit their homes and check on their welfare. For undocumented immigrants and families of color – during the height of Black Lives Matter protests – that was often problematic, the researchers say.

While most impacts reported by respondents were negative, there were a few silver linings: Many kids who had been bullied or experienced racism at school found a better learning environment at home.

The researchers are extending the model they used to other communities that want to identify and address deleterious effects of the dual pandemics – racism and COVID-19 – including Eagle County. One common problem they see among educators in general is a tendency to be “color-blind,” by either denying that race is an issue or insisting that they treat every student equally. The effort to address racism needs to be an ongoing process, not a single workshop.

“Often this is a one- or two-day training, and then it stops,” Jones said. “There is not always follow-through.”

A self-service model

“How do we redesign systems, like the education system, so they stop perpetuating racism?” Williford asked. “We want to bring tools to these other communities and let them be the driver, in terms of how they conceptualize the challenges they’re facing and what they would do about it. We’re equipping folks with skills they can then take on themselves.”

“People are way more invested if they’re working on their own ideas,” Jones added. “There is a problem we see all the time, which is only talking about individual people learning not to be color-blind, for instance. That is not going to make the change. We need to actually codify anti-racism and systems, and not just say, ‘Everyone, try and be less racist.’”

Meanwhile, a bill that is working its way through the state legislature would establish a temporary program to facilitate youth access to mental health services before the fall. Williford and Jones shared the results of their survey with one of the sponsors of HB-1258, Rep. Dafna Michaelson Jenet, a Democrat representing House District 30.

In addition to Jones and Williford, students Kaylee Becker and Samantha Bruick – two of Jones’ graduate research assistants pursuing master’s degrees in social work – contributed to the project. Other contributors were Marie Zamzow of the School of Social Work and Melissa George and Rebecca Toll of the Department of Human Development and Family Studies.

The School of Social Work and Department of Human Development and Family Studies are part of CSU’s College of Health and Human Sciences.